IGJ – Monitoring Article on FTAs

Report from the United Kingdom

Rinda Amalia., SH., MH

Fellow Researcher of IGJ

Following the signing of the second round of Indonesia/UK Joint Trade Review between International Trade UK and the Indonesian Ministry of Trade on 20-21 July 2020, which was delegated by the Directorate of Bilateral Trade Agreement Relations, Cathryn Law and HM the Commissioner of Trade for Asia Pacific Natalie Black, where in the contents of the signing, the main reason is related to an unexpected common problem, namely Covid-19, as well as to improve the economic situation of the two countries, specifically in the trade and investment sector.[1]

Something that deserves the attention is that in this pandemic, both the UK and Indonesian parties continue to implement agreement negotiations, which means that Indonesia’s position is considered quite important in the map of international trade in the UK. Based on the official UK government broadcast on Gov.UK, in 2019, the total trade in goods and services between the UK and ASEAN was £41.7bn, which is the highest in 10 years. Meanwhile, the UK total trade with Indonesia alone was worth around £ 2.9bn in 2019.

The position of Indonesia is considered highly prestigious by Her Majesty’s Commissioner of Trade for Asia Pacific, Natalie Black CBE, who stated, “I am extremely happy with the UK-Indonesia trade review discussion which is developing well. Indonesia is a key partner of the UK and we are eager to conduct further bilateral trade talks on trade and investment which will be implemented in various key sectors, including professional services, pharmaceuticals, energy, education and technology”. Furthermore, she revealed that, “we will take a closer look at the collaboration between these two countries and work together to form a dynamic cooperation between the UK and ASEAN and the Southeast Asia Region”.

Indonesia is one of the most rapidly growing economies, a member of the G20 and one of the largest economies in ASEAN and moreover it is the 4th (fourth) country with the largest population in the world and is predicted to be in the 5 (five) largest world economy in 2050.

The Trading Map of Indonesia – UK

Quoted from Embassy of The Republic of Indonesia in London,[2] the cooperation between the UK and Indonesia is not only in the trade and investment sectors, but also in the study forum discussions. In the two-way trade sector, UK is recorded as the top 5 foreign trade partners with trade records[3] in 2015: US$ 2.34 billion, 2014: US$ 2.55 billion, and 2013: US$ 2.72 billion. For investments conducted in Indonesia, UK is the top 10 foreign investment partners for Indonesia with records as follows 2015: US$ 503.22 million (267 projects), 2014: US$ 1.59 billion (182 projects), 2013: US$ 1.08 billion (231 project). Meanwhile, the UK and Indonesia study forum project discusses important issues such as the following:

- Partnership Forum;

- Annual Trade Talks;

- Energy Dialogue;

- Joint Working Group on Education;

- Joint Working Group on Creative Industries;

- Navy to Navy Strategic Meeting

This was reaffirmed at an event organized by the British Foreign Policy Group[4] and the Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia which was held on 9 July, 2019, of which was held to commemorate 70 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries. This seminar entitled “The Future of Indonesia-UK Relations Post Brexit” was opened by the Ambassador of the Republic of Indonesia to UK, H.E Dr. Rizal Sukma and attended by Dr. Champa Patel, the Chair of the Asia Pacific Program, H.E Dr. Dino Patti Djalal, the Chairperson of the Policy-Making Community in Indonesia, Richard Graham MP, the Chair of APPG in Indonesia, Martin Hatfull, the Chair of the Anglo-Indonesian Society and Former Ambassador to Indonesia, Orlando Edward, the Regional Manager of the British Council Global Network Team.

This was reaffirmed at an event organized by the British Foreign Policy Group and the Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia which was held on 9 July, 2019, of which was held to commemorate 70 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries. This seminar entitled “The Future of Indonesia-UK Relations Post Brexit” was opened by the Ambassador of the Republic of Indonesia to UK, H.E Dr. Rizal Sukma and attended by Dr. Champa Patel, the Chair of the Asia Pacific Program, H.E Dr. Dino Patti Djalal, the Chairperson of the Policy-Making Community in Indonesia, Richard Graham MP, the Chair of APPG in Indonesia, Martin Hatfull, the Chair of the Anglo-Indonesian Society and Former Ambassador to Indonesia, Orlando Edward, the Regional Manager of the British Council Global Network Team.

At this meeting, several important issues were discussed; the first issue was about China and Geopolitical Relations. Richard Graham MP said that improving relations with China would be beneficial for both countries. Dr. Dino Patti Djalal noted that trade between Indonesia and China is slowly increasing and is expected to reach $1000 billion for the next year, meanwhile trade with the US has decreased, most recently only worth around $16 billion. Martin Hatfull noted that it would be difficult for the UK and Indonesia to focus on bilateral relations, since the UK is occupied with Brexit and Indonesia is focusing on ASEAN.

The second issue is regarding education. Orlando Edwards provides an interesting explanation on how Indonesia-UK relations can be improved through education. He outlined opportunities to engage with Indonesia through transnational education programs, such as teaching UK university programs in Indonesia, or programs shared between Indonesia and the UK. Furthermore, he highlighted the British Council’s work in advancing the cultural sector in Indonesia, with the recently held arts festival for people with disabilities in Indonesia, which has now become an annual event. In the UK, Indonesian culture is promoted through events including the London Book Fair. Richard Graham also stressed the need to strengthen the relationship of the people between the two countries. He said there was a need to shift individual awareness about other nations beyond tourism, to the school and university experience. Martin Hatfull added that there is a need to attract more UK students who are interested in studying in Indonesia, since there has been an increase in Indonesian students studying in the UK, which has not been matched in other ways. Dr Djalal echoed this point and added that the difficulty lies with the Indonesian student visa system, as the country is not widely open to foreign students wishing to study or conduct researches in Indonesia. Moreover, he noted that currently there are only about 5,000 Indonesian students in the UK, which is far more studying in Australia. Education openness will be the key to strengthening relations of both countries.

This was reaffirmed at an event organized by the British Foreign Policy Group and the Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia which was held on 9 July, 2019, of which was held to commemorate 70 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries. This seminar entitled “The Future of Indonesia-UK Relations Post Brexit” was opened by the Ambassador of the Republic of Indonesia to UK, H.E Dr. Rizal Sukma and attended by Dr. Champa Patel, the Chair of the Asia Pacific Program, H.E Dr. Dino Patti Djalal, the Chairperson of the Policy-Making Community in Indonesia, Richard Graham MP, the Chair of APPG in Indonesia, Martin Hatfull, the Chair of the Anglo-Indonesian Society and Former Ambassador to Indonesia, Orlando Edward, the Regional Manager of the British Council Global Network Team.

At this meeting, several important issues were discussed; the first issue was about China and Geopolitical Relations. Richard Graham MP said that improving relations with China would be beneficial for both countries. Dr. Dino Patti Djalal noted that trade between Indonesia and China is slowly increasing and is expected to reach $1000 billion for the next year, meanwhile trade with the US has decreased, most recently only worth around $16 billion. Martin Hatfull noted that it would be difficult for the UK and Indonesia to focus on bilateral relations, since the UK is occupied with Brexit and Indonesia is focusing on ASEAN.

The second issue is regarding education. Orlando Edwards provides an interesting explanation on how Indonesia-UK relations can be improved through education. He outlined opportunities to engage with Indonesia through transnational education programs, such as teaching UK university programs in Indonesia, or programs shared between Indonesia and the UK. Furthermore, he highlighted the British Council’s work in advancing the cultural sector in Indonesia, with the recently held arts festival for people with disabilities in Indonesia, which has now become an annual event. In the UK, Indonesian culture is promoted through events including the London Book Fair. Richard Graham also stressed the need to strengthen the relationship of the people between the two countries. He said there was a need to shift individual awareness about other nations beyond tourism, to the school and university experience. Martin Hatfull added that there is a need to attract more UK students who are interested in studying in Indonesia, since there has been an increase in Indonesian students studying in the UK, which has not been matched in other ways. Dr Djalal echoed this point and added that the difficulty lies with the Indonesian student visa system, as the country is not widely open to foreign students wishing to study or conduct researches in Indonesia. Moreover, he noted that currently there are only about 5,000 Indonesian students in the UK, which is far more studying in Australia. Education openness will be the key to strengthening relations of both countries.

The third issue is about trade. Martin Hatfull said the UK’s track record in identifying sectors to prioritize in terms of exports and investment was not satisfying, and that the country had to take a long-term view. He said that a joint task force could be formed to observe how the two countries could make the most of the trade relationship, with Indonesia prioritizing UK infrastructure and human resources. Dr. Djalal noted that a good way to build economic relations is through technology sharing and innovation from the UK to Indonesia. He added that the main stumbling block to improving trade relations was visa issues – the visa fee for his family of five to go to the UK was more than half the cost of his ticket. Martin Hatfull agrees that the visa issue is a key to trade as well.

In building UK-Indonesia trade relationship, the speaker emphasized the importance of caring for the environment. Richard Graham MP highlighted climate change as an increasingly important issue for Indonesia and the UK. Martin Hatfull said coordinating the climate agenda could be a “quick win” for strengthening ties. On the topic of palm oil, Dr. Djalal provided an account of the radical shift in Indonesia’s position on palm oil since the 1970s, from one of the world’s worst rates of deforestation, to working with the international community to promote corporate discipline on this issue.

The GeoPolitical and Economic Map of the UK for Indonesia following Brexit

The interpretation of foreign policy is often used regarding diplomacy, but in fact it includes everything that the governments do abroad to secure national security, prosperity, influence and trust from the outside world in the country itself.[5] The same is implemented by Indonesia and UK. It definitely makes sense if the two parties mutually conduct diplomation and negotiate to gain the best for their respective countries, what remains now is only upon how strong the position of the country is; what is the appeal and bargaining power of each country.

Brexit is a combination of British and Exit which refers to the meaning of the UK resignation from the European Union, following the referendum held in June 2016 by David Cameron 51.9% of the UK public voted to leave the EU. This referendum is the second UK referendum during David Cameron’s administration. Then, the negotiations continued from 2018 to 2019 to discuss technical matters which needed to be resolved. In March 2019, the UK Parliament asked the government to postpone the Brexit date to April, then to October, due to the Parliament considered the government’s promptness to be minimal to implement this Brexit. In July 2019, due to constant rejection of her proposals, Theresa May stepped down, being replaced by Boris Johnson, who was also one of the strongest supporters of Brexit since its early days.

On 31 October 2019, eventually an agreement was reached on one important part of Brexit, yet with some reasons to study it further, the UK Parliament again refused to ratify it, thus it went back past the previously set October limit. However, in December 2019, when general elections were held again in the UK, the Conservative Party supporting the government received immensely strong support from the people, therefore it took back control of the UK Parliament, which greatly paved the way for Boris Johnson to leave the European Union. 31 January 2020 is the date when the UK would officially leave the European Union. In terms of negotiations, there are many things which have not been agreed upon, but through a vote in the European Union Parliament on January 29, it was agreed that there would be a transitional period in which all the previous regulations would remain in effect while negotiations continued, and it is estimated that this transitional period will continue until the end of the year on 31 December 2020. Previously, on 23 January, the UK Parliament which is now controlled by government supporters and Boris Johnson have ratified the resignation agreement.[6]

The Economic Growth of the UK

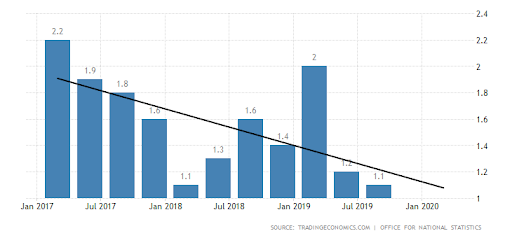

The UK economic growth has been trimmed by the Bank of England (BOE) on 30 January 2020 from 1.2% to 0.8%. This trimming occurred due to the uncertainty factor in trade developments following the implementation of Brexit. The pace of UK economic growth itself from the Brexit referendum to the end of 2019 tended to decline from around 2% to 1.1% Year on Year in the third quarter of 2019.

Furthermore, the monarchy’s economic growth was reported to have shrunk by 0.3% in November 2019. The manufacturing index fell 1.7% in November, while the services index, which accounts for 80% of the economy, has fallen 0.3%. Business investment has also declined since the third quarter of 2017, until at least mid-2019. Meanwhile, productivity performance was reportedly at its weakest point in history until the third quarter of last year. The comprehensive descriptions and data above show the decline in the performance of the UK economy ahead of the Brexit and tend to be gloomy prospects after the Brexit. The domino effect will be experienced on the Eurozone economy which is struggling to deal with regional recession pressures. And when the Chinese economy is increasingly being hit by the corona virus outbreak, the economic downturn in these three major financial locations in the world will also have an impact on the global economy which is marked by uncertainty. This seems to add to the global instability facing 2020, coupled with the issue of the virus outbreak and Middle East geopolitical tensions. For Indonesia, this is an increasingly severe external challenge for economic growth. Meanwhile, Fitch Ratings as an international rating agency recently maintained Indonesia’s rating at the BBB level/stable outlook (Investment Grade), partly because Indonesia’s economy is recognized as tough or resilient amid the dynamics of the global economy. It is acknowledged that Indonesia’s economy will remain resilient, or tough, in the future, supported by the infrastructure programs and reforms under the administration of President Jokowi.[7]

Well, the emerging question is, regarding the post-Brexit geopolitical and economic position of the UK which remains expecting and guessing coupled with the situation of the Covid pandemic, why do these two countries continue to implement the Joint Trade Review? Will this benefit Indonesia more or the UK towards Indonesia as a field for new profit? Is it possible in a bilateral agreement to reach a win-win solution for both parties? In a matter of fact, thus far bilateral trade agreements tend to be tighter and not profitable for countries with weaker bargaining positions. Moreover, the nature of this type of agreement is usually tightly closed, which is intended to avoid public discussion of which is feared to cause the hidden agenda of the agreement to fail. For this reason, meticulousness is needed in observing what the hidden intentions of the UK are in this very agreement.****

[1] Retrieved from www.gov.uk, accessed on 18 August 2020

[2] Embassy of The Republic of Indonesia in London, The United Kingdom Accredited to Republic of Ireland and IMO., Indonesia-UK Relations., www.kemlu.go.id., downloaded on 26 September 2020

[3] ibid

[4] British Foreign Policy Group., The Future of Indonesia – UK Relations Post Brexit., https://bf[g.co.uk., downloaded on 26 September 2020

[5] Retrieved from Britsh Global Review www.csis.org on 18 August 2020

[6] Daniel Sumbayak., Brexit: UK Resmi Keluar Uni Eropa, Masalah Selanjutnya?., www.vibiznew.com., downloaded on 26 September 2020

[7] ibid